January is a special time for Pittock Mansion. After the bustle and merriment of our popular Christmas display, the Mansion closes and undergoes a deep cleaning in addition to the maintenance and repair projects that cannot be done while we are open to the public. It is a time when the wear and tear of the past year is washed away and the Mansion is restored and made ready to welcome the next year’s visitors.

The following article is from the Winter/Spring 2019 edition of our member newsletter, Pittock Papers. It is Part Two of the three-part series “Pittock Mansion: The Collection.”

Pittock Mansion: The Collection

Part Two: Preservation

One of the unique and fascinating things about historic house museums is that they were homes first, museums second. And Pittock Mansion is no different. While Henry Pittock built a technologically advanced home for 1914, air conditioning was rare. Nor were the Pittocks concerned with screening the numerous windows that opened to the surrounding landscape during the summer. The result? Sun, heat, bugs, and debris from trees were all allowed to come in and make themselves at home.

Fast forward to today and what was once a personal item from the late 19th or early 20th century is now an artifact in a house museum. And different objects—such as a piece of wood furniture, a lace dress, or a silver tea set—require different approaches to care. For the Mansion, the main goals when cleaning or conserving an artifact are threefold: 1) prevent further damage or deterioration by removing dust and dirt, protecting it from sunlight and curious hands, and sometimes hiring a conservator to stabilize the object; 2) when possible, choose conservation approaches that are reversible; and 3) balance maintaining the authenticity and history of a piece while also trying to present the house as it may have looked 100 years ago.

“Our biggest challenges to artifact preservation,” Curator Patti Larkin explains, “are space, climate control, things being loved to death, and limited disaster protection.” With space, the Mansion works to use what storage space is available more efficiently and be selective about what is added to the collection. As for things being “loved to death,” Larkin points out that care and placement play a vital role. For example, “historic textiles are fragile…and we try to rotate the more fragile pieces off display to reduce light exposure.” As for silver pieces, Larkin emphasizes that polishing removes some of the metal each time therefore it is done sparingly. “We avoid polishing rarer pieces, storing them in cabinets that slow the rate of tarnishing instead,” she concludes.

As a general approach to cleaning artifacts, Larkin states that the Mansion mostly relies upon vacuuming and dusting. “We consciously determine how and what we clean based on the expertise it requires, and the potential effects of cleaning on the artifacts or house,” she continues. Larkin goes on to stress that any cleaning that involves cleansers or polishing should be done only by trained, qualified conservators. Taking it a step further, the Mansion also brought in a specialized conservator to train staff how to safely vacuum and dust objects, furnishings, textiles, and rugs.

While climate control might be seen as one of the biggest challenges to artifact preservation, the Mansion strives to do what it can to reduce the negative effects. Throughout the day, staff strategically closes shades to limit light exposure and heat. In addition, the Mansion has also applied a UV film on the windows, but Larkin did point out that “it’s reaching the end of its useful life and will need to be replaced.” In addition, conserved drawings or paper ephemera on display have been encased with archivally appropriate matting and UV-blocking glass or Plexiglass.

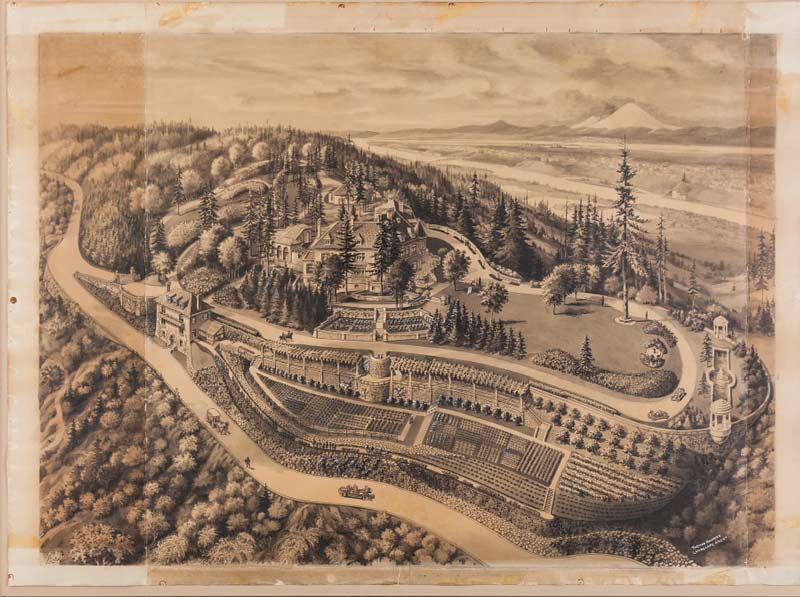

The recently conserved 1913 landscape drawing.

A recent project also brought up the question of how far the museum should go when it comes to restoring a historical object. In the case of the recent conservation of a landscape drawing currently on view in the Mansion’s lower level, the Mansion’s Collections Management Committee and Larkin discussed treatment options with the conservator. The Mansion had discovered that the drawing had been folded around a piece of cardboard—which is very acidic and damaging to paper—and the conservator could have retouched the parts that had been worn off from the folding.

The Mansion, however, opted not to. As Larkin explains: “We decided that the damage was part of its history. It told the story of what had happened to the drawing, and we thought the piece was more notable as a historical artifact then as a fully restored piece of art.”

The Mansion’s approach to preservation care can be summed up as one that incorporates thoughtful deliberation and careful consideration. “There is a cost to store and preserve and save artifacts,” Larkin notes, “and we’re trying to avoid creating future conservation problems.” And for the Mansion, our supporters, and all of our visitors who get to engage and experience the museum’s collection—it’s worth it.